The 340B Discount Program: Current Landscape & Key Trends

What is the 340B Drug Discount Program?

The 340B Drug Discount Program requires pharmaceutical manufacturers participating in Medicaid to provide eligible outpatient drugs at significantly reduced prices to eligible healthcare facilities, known as 340B CEs. The program was established in 1992 under the Veterans Health Care Act and is overseen by the Office of Pharmacy Affairs (OPA) within the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The legislative intent of the program was to assist providers serving significant low-income and uninsured populations in stretching their resources to improve care.

Key 340B Program Terms Defined

Understanding the 340B Drug Discount Program requires familiarity with key terminology and covered entities. Here are essential definitions to help clarify core concepts.

340B Covered Entities (CEs)

CEs are qualifying health care sites that register with HRSA to participate in the 340B program to purchase discounted prescription drugs based on characteristics of the population they serve including1:

- Health Centers: Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) , Native Hawaiian Health Centers, Tribal/Urban Indian Health Centers , Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Grantees

- Hospitals: Disproportionate share hospitals (DSHs), certain pediatric and cancer hospitals, sole community hospitals, rural referral centers, and critical access hospitals (CAHs)

- Specialized clinics: Black Lung Clinics, Comprehensive Hemophilia Diagnostic Treatment Centers, Family Planning Clinics (Title X), Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinics, and Tuberculosis Clinics

Disproportionate Share Hospitals

A non-profit or government hospital that qualifies for the 340B program if the percentage of Medicare inpatient days attributable to patients eligible for both Medicare Part A and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Medicaid, and/or who uninsured is at least 11.75%.2

Child Sites

CEs that purchase or own other outpatient facilities may register those facilities with HRSA as child sites. Examples of child sites include smaller hospitals and physician practices acquired by parent sites. Child sites have access to 340B discounted drugs for their office administration and outpatient dispensing.

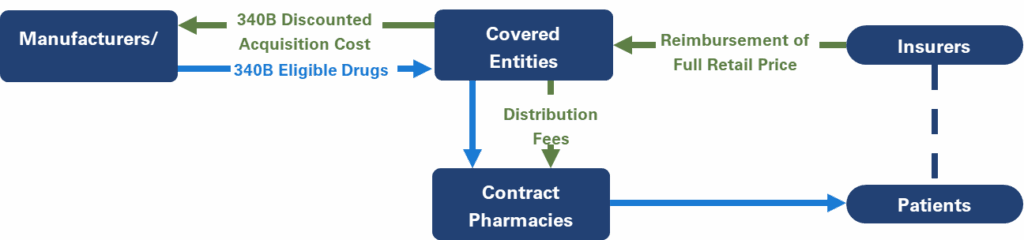

Contract Pharmacies

340B CEs may dispense 340B discounted drugs to patients through an in-house pharmacy or through a retail or specialty pharmacy under agreement to dispense drugs to patients on its behalf, known as a contract pharmacy. CEs and contract pharmacies may enter “ship to/bill to” arrangements, in which discounted drugs purchased by the CE are shipped directly to the contract pharmacies. Contract pharmacies increase the geographical reach of the population that receives 340B discounted drugs, increasing 340B revenue for both the CE and the contract pharmacy.

Eligible Patients

Under the statutory definition, an eligible 340B patient is one who receives healthcare services from a covered entity recognized under the 340B program.

Understanding 340B Discounts

Learn how discounts under the 340B program are determined, calculated, and administered.

How are 340B Discounts Calculated and Administered?

Unlike other programs, which bill manufacturers for rebates after a drug is dispensed, 340B CEs purchase drugs from the wholesaler at the discounted 340B price. The 340B purchase price is determined based on commercial discounts given by manufacturers, as well as price increases, similar to Medicaid rebate calculations; these discounts are calculated to create a ceiling price, or the maximum price paid by a CE for each drug. The ceiling prices are not publicly available, but at launch, 340B discounts on brand drugs are the Medicaid minimum of 23.1% for brand drugs.3 Following the Medicaid formula, the 340B purchase price takes into consideration the negotiated best commercial price for the drug and gives credit for price increases over the consumer price index (CPI). Negotiated commercial discounts increase as a drug is on the market longer and competition in the class becomes a factor, and the price increase penalty is cumulative, resulting in 340B prices that are frequently >50% below the list price after a few years on the market, generating substantial cost savings.4

Managing Duplicate Discounts in the 340B Program

Duplicate discounts can occur when 340B purchased drugs are dispensed to Medicaid patients. Following claim processing, the Medicaid program bills manufacturers post-dispensing for rebates on those claims. When a CE bills Medicaid for the dispensing of a 340B discounted drug, the manufacturer is then required to provide the discounted purchase price to the CE and provide the state with the mandated Medicaid rebate, in violation of program rules. With the implementation of the IRA’s Drug Price Negotiation Program, duplicate discounts may also occur when 340B purchased drugs are dispensed to Part D patients and subject to a maximum fair price (MFP); the MFP is adjudicated post-dispensing and, in this case, paid to the pharmacy. For a MFP product, the 340B price and the discount provided to equal the MFP will likely not be the same but still results in the manufacturer providing significant discounts two times – one at purchase and one post-dispensing.

340B Program Growth: Child Sites and Contract Pharmacies

Since its inception, the 340B program has expanded significantly. In 1992, there were 392 registered 340B CEs and as of 2023 there were more than 56,500 CEs, the majority of which are hospitals.5 The expansion of CEs is paralleled by the expansion of registered child sites. There were 179 registered 340B child sites in 1992, growing most significantly in the last decade from 6,630 in 2010 to 48,407 in 2023.5

Neither HRSA nor the OPA limits the number of pharmacies with which a CE may contract, and the number of contract pharmacies are growing rapidly, increasing from 789 in 2009 to 25,775 in 2022.6 In a review of the 340B program, the GAO found that 69.3% of 340B hospitals had at least one contract pharmacy.7 Based on the number of outside pharmacies registered as CEs with HRSA, each DSH had an average of 25 contract pharmacies in 2017.7 However, the actual number is likely higher because CEs are not required to register all arrangements. The GAO estimates the actual number of contract pharmacy arrangements could be as high as 34 times the number reported to HRSA.7

The growth of the 340B program is driving increased 340B purchasing, which has increased 19% annually from 2010 to 2021.8 In 2023, covered entities purchased $66.3 billion in covered outpatient drugs, the majority of which, $51.9 billion, was purchased by DSHs.9

What are the Key Factors Driving 340B Growth?

- Patient Definition: Patients eligible for 340B discounted drugs must have a patient-provider relationship with a 340B CE, but the requirements to meet this relationship are intentionally broad and somewhat vague.

- Pricing of Dispensed 340B Drugs: CEs dispensing discounted drugs are not required to pass the discounted price through to patients or payers. Prescriptions dispensed to insured patients provide a large margin of profit for 340B entities, as insurers reimburse based on the wholesale acquisition cost, not at the 340B price. Cash-paying patients may see a discounted price, but this is not required.

- 340B DSH Eligibility Formula: The threshold of uninsured, Medicare, Medicaid, and low-income patients required for DSHs is 11.75%, allowing many hospitals to qualify. Increases in Medicaid and Medicare enrollment can result in even more hospitals qualifying.

- Contract Pharmacy Proliferation: Contract pharmacies are not required to be located in the vicinity of the CE and are frequently several miles away. The locations of many contract pharmacies are in much more affluent areas, with a majority of patients being commercially insured. However, by definition, a patient who received services from the CE and qualifies as a “patient” is permitted to receive 340B discounted drugs. In these cases, commercial payers reimburse the 340B contract pharmacies based on the agreed upon formula, and the contract pharmacies retain the additional margin realized as a result of the significantly lower 340B purchase price.

Use of 340B Program Savings

Ideally, hospitals and other CEs share the savings on drugs purchased at 340B prices with patients (i.e. discounted prices for cash-paying/uninsured patients) and reinvest the revenue from dispensed and administered 340B drugs to expand and improve patient services. However, no current laws, regulations, or guidance specifically require savings from drug discounts be passed directly to patients at point of sale, nor do they dictate how revenue accrued from the program should be allocated. Research has shown that despite the 340B program’s growth, many DSH hospitals are not providing levels of charity care in line with the increases in 340B revenue.10,11 The national average of charity care for all short-term acute care hospitals is 2.5%, however 69% of DSHs provide less than that amount.10 The profits associated with dispensing discounted 340B drugs has shifted treatment from non-340B physician office settings to the 340B outpatient settings and their child sites.

340B: Policy Reforms and Market Implications

Explore recent changes in the 340B landscape and their implications for stakeholders.

Manufacturers’ Policies Impacting Contract Pharmacies

In 2020, in response to proliferation of CEs and lack of HRSA guidance and oversight, some manufacturers instituted one or more of the following contract pharmacy policies:

- Limited contracts (quantity): limiting the number of contract pharmacies associated with a covered entity (usually to 1-2 pharmacies), usually when the CE does not have an in-house pharmacy. CEs with in-house pharmacies would not be permitted any contract pharmacies.

- Limited contracts (radius + quantity): limiting the number of contract pharmacies to a certain radius of the covered entity (i.e.. one pharmacy within a 40-mile radius)

- Limited distribution: restrict distribution from CE to contract pharmacies; require direct distribution from the manufacturer (for specified products)

Several policies contain provisions that allow exceptions to contract pharmacy limitations if the covered entity agrees to provide claims data to the manufacturer via the 340B Eligibility and Submissions Portal (ESP) platform.

There are ongoing lawsuits between manufacturers and HRSA due to misalignment on the role of contract pharmacies and the ability of manufacturers to take action to limit use and sales.

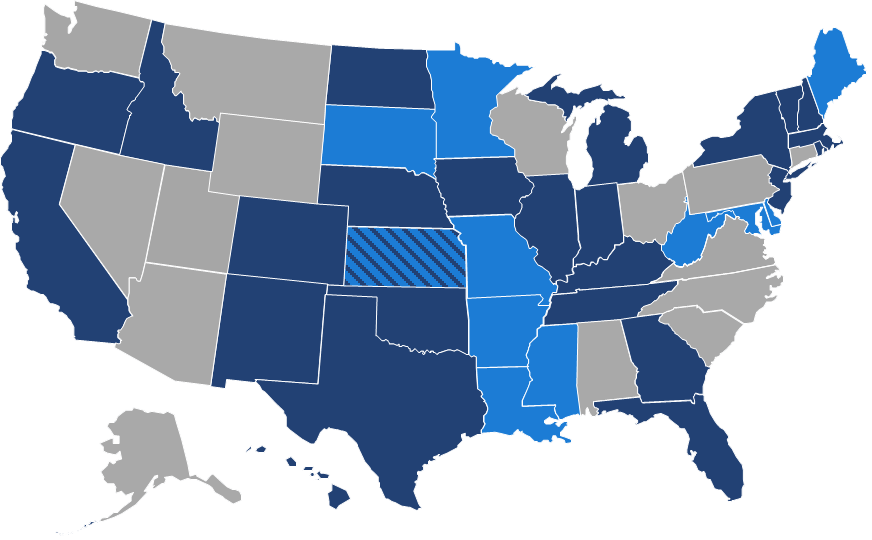

State Policies Influencing 340B

Since 2021, 10 states have enacted laws to counter drug manufacturers’ policies restricting sales to contract pharmacies and a total of 25 states have introduced similar bills.

Opportunities for Federal Reform of the 340B Program

The scope and growth of the 340B program remain an issue of disagreement, with stakeholders concerned with the program’s expansion, limited regulatory oversight, and alignment with the original mission. Future reforms may address transparency requirements, patient definition, duplicate discounts as related to MFP drugs, and contract pharmacy oversight.

Contact us today to explore how our team can help you stay updated on 340B policy reforms and litigation and understand how these changes may impact your market access strategy.

References:

- 340B eligibility. HRSA. June 2024. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration.

- Disproportionate Share Hospitals. HRSA. June 2024. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration/hospitals/disproportionate-share-hospitals.

- Unit rebate amount information. Medicaid. January 15, 2025. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/medicaid-drug-rebate-program/unit-rebate-amount-calculation.

- GAO. Drug Pricing: Manufacturer Discounts in the 340B Program Offer Benefits, but Federal Oversight Needs Improvement. September 2011. Accessed April 21, 2025: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-11-836.pdf.

- Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) OPIAS 340 Data. Accessed January 31, 2025.

- Nikpay S, McGlave CC, Bruno JP, Yang H, Watts E. Trends in 340B Drug Pricing Program Contract Growth Among Retail Pharmacies From 2009 to 2022. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(8):e232139. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.2139

- GAO. Drug Discount Program: Federal Oversight of Compliance at 340B Contract Pharmacies Needs Improvement. June 2018. https://www.gao.gov/assets/d18480.pdf

- Sachs R, Varcie J. Spending in the 340B Drug Pricing Program, 2010 to 2021. June 17, 2024. Presented at: Conference of the American Society of Health Economists. Accessed April 21, 2025: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-06/60339-340B-Drug-Pricing-Program.pdf.

- 2023 340B covered entity purchases. HRSA. October 2024. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/updates/2023-340b-covered-entity-purchases.

- Alliance for Integrity & Reform of 340B. Charity Care at 340B Hospitals is on a Downward Trend. October 2023. Accessed April 21, 2025: https://340breform.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023-Charity-Care-Report-Final-1.pdf

- GAO. Needed to Reduce Financial Incentives to Prescribe 340B Drugs at Participating Hospitals. June 2015. Accessed April 21, 2025: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-15-442.pdf.

Related Content: